Read the Latest

TopicsStories

Educational Resources

- Projects

- Events

- Our Team

- Stories and Resources

- Latest Stories

- Topics

- Educational Resources

- Newsletter

- Connect

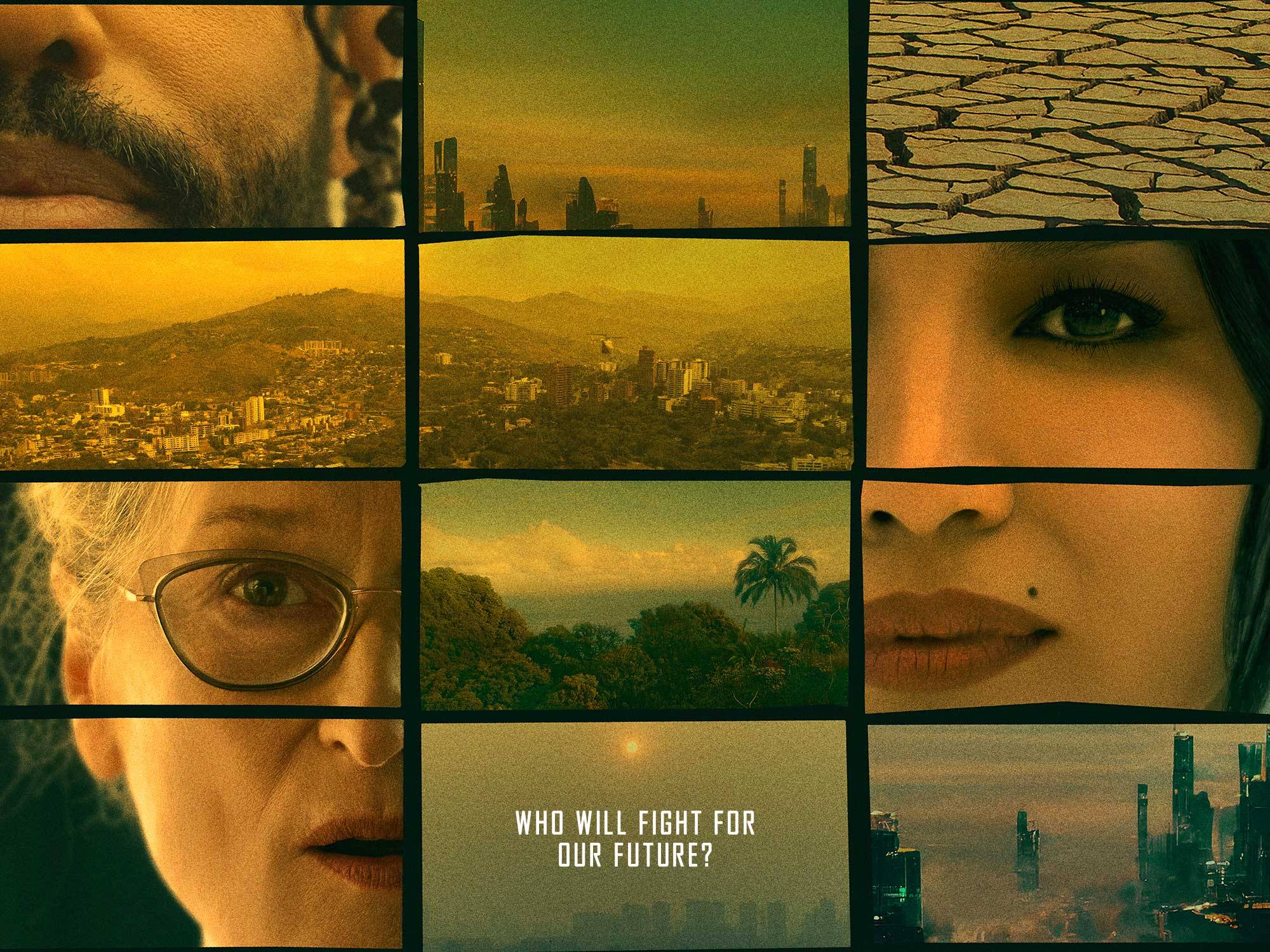

Series creator Scott Z. Burns talks about how rising temperatures will change life in the near future