Getty Images

Read the Latest

- Wars Like Ukraine and Iran Are Pushing Countries To Rethink How They Get Their Energy

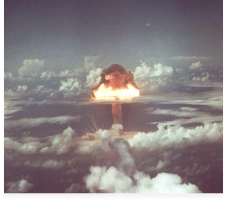

- Iran’s nuclear ambassador alleges that US-Israeli airstrikes targeted the Natanz enrichment facility

- The nuclear nightmare at the heart of the Trump-Anthropic fight

- UN nuclear watchdog says it’s unable to verify whether Iran has suspended all uranium enrichment

- Companies Are Choosing Efficiency Over Bold Climate Goals

TopicsStories

Educational Resources

- Projects

- Events

- Our Team

- Stories and Resources

- Latest Stories

- Wars Like Ukraine and Iran Are Pushing Countries To Rethink How They Get Their Energy

- Iran’s nuclear ambassador alleges that US-Israeli airstrikes targeted the Natanz enrichment facility

- The nuclear nightmare at the heart of the Trump-Anthropic fight

- UN nuclear watchdog says it’s unable to verify whether Iran has suspended all uranium enrichment

- Companies Are Choosing Efficiency Over Bold Climate Goals

- Topics

- Educational Resources

- Newsletter

- Connect