Read the Latest

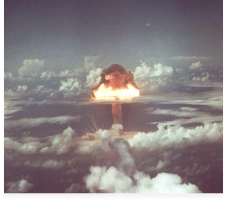

- Revisiting ‘Threads’ – Director and Star Reflect on the 1984 Nuclear Apocalypse TV Movie and Its Enduring Impact

- The Global Axis of Climate Leadership Has Shifted

- America Can’t Do to North Korea What It Just Did to Iran

- Millions of Americans believe they’re safe from wildfires in their cities. New research shows they’re not

- Nuclear weapons woes: Understaffed nuke agency hit by DOGE and safety worries

Educational Resources

- Projects

- Events

- Our Team

- Stories and Resources

- Latest Stories

- Revisiting ‘Threads’ – Director and Star Reflect on the 1984 Nuclear Apocalypse TV Movie and Its Enduring Impact

- The Global Axis of Climate Leadership Has Shifted

- America Can’t Do to North Korea What It Just Did to Iran

- Millions of Americans believe they’re safe from wildfires in their cities. New research shows they’re not

- Nuclear weapons woes: Understaffed nuke agency hit by DOGE and safety worries

- Topics

- Educational Resources

- Newsletter

- Connect