Netflix

Read the Latest

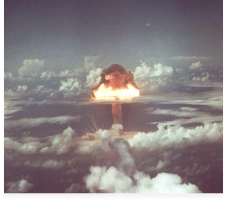

- Is a new US-Russia arms race about to begin?

- Let the Arms Race Begin

- Sixty years later, Spain grapples with one of the most notorious nuclear weapons disasters in history

- The Climate and Energy Implication Hidden in Mark Carney’s Davos Speech

- Scientists race to protect Lake Superior from invasive mussels

TopicsStories

Educational Resources

- Projects

- Events

- Our Team

- Stories and Resources

- Latest Stories

- Is a new US-Russia arms race about to begin?

- Let the Arms Race Begin

- Sixty years later, Spain grapples with one of the most notorious nuclear weapons disasters in history

- The Climate and Energy Implication Hidden in Mark Carney’s Davos Speech

- Scientists race to protect Lake Superior from invasive mussels

- Topics

- Educational Resources

- Newsletter

- Connect