Read the Latest

- Companies Are Choosing Efficiency Over Bold Climate Goals

- What to know as US moves military assets to Mideast and Iran nuclear talks have yet to reach a deal

- Saudi Arabia may have uranium enrichment under proposed deal with US, arms control experts warn

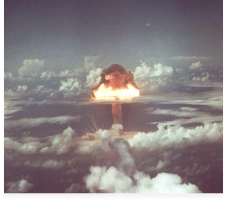

- Trump Risks Igniting a Nuclear Wildfire

- The World Needs China’s Climate Technology. That’s the Dilemma

TopicsStories

Educational Resources

- Projects

- Events

- Our Team

- Stories and Resources

- Latest Stories

- Companies Are Choosing Efficiency Over Bold Climate Goals

- What to know as US moves military assets to Mideast and Iran nuclear talks have yet to reach a deal

- Saudi Arabia may have uranium enrichment under proposed deal with US, arms control experts warn

- Trump Risks Igniting a Nuclear Wildfire

- The World Needs China’s Climate Technology. That’s the Dilemma

- Topics

- Educational Resources

- Newsletter

- Connect