Read the Latest

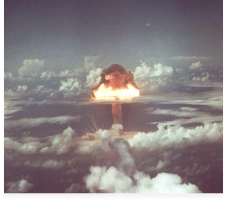

- Stop Iran’s Nuclear Threat With a Deal, Not Conflict

- ‘Everything we had floated away’: Hurricane Helene survivors help each other as disinformation swirls

- ‘Turning Point’ Docuseries Deconstructs The Cold War and Warns of Another

- Federal Firings Threaten Great Lakes’ $5 Billion Fishery

- Amid new Trump era, South Korea considers ‘plan B’ – building its own nuclear weapons

Educational Resources

- Projects

- Events

- Our Team

- Stories and Resources

- Latest Stories

- Stop Iran’s Nuclear Threat With a Deal, Not Conflict

- ‘Everything we had floated away’: Hurricane Helene survivors help each other as disinformation swirls

- ‘Turning Point’ Docuseries Deconstructs The Cold War and Warns of Another

- Federal Firings Threaten Great Lakes’ $5 Billion Fishery

- Amid new Trump era, South Korea considers ‘plan B’ – building its own nuclear weapons

- Topics

- Educational Resources

- Newsletter

- Connect